Performance#

When you are choosing a computer, how should you choose? Is it the computer that performs operations the fastest, one that does the most work, or the one that consumes least power?

In data centers where they have a lot of jobs submitted by many users, they would care about the throughput or bandwidth - the total amount of work done in a given time. For example, which computer completed the most amount of jobs at the end of the day?

For us, individual users, we want to reduce the response time or the execution time - the time from start of a program to the end of a program.

$$ \text{Performance} = \frac{1}{Execution \space time} $$

From the math equation, we see that the smaller the execution time is, the higher the performance.

Now, let’s look at how we can determine the execution time. But first, let’s understand what is the execution time. We call this wall clock time, response time, or elapse time. It measures the total time for a task: disk accesses + memory accesses + i/o activities + operating system overhead.

But it is common that computers are shared, and processors work on the multiple programs simultaneously. In that case, systems try to optimize throughput rather than time for one program. From that stems the distinction between elapsed time and CPU execution time or just CPU time.

CPU time is further divided to user CPU time and system CPU time. We call the respective performances: CPU performance and system performance.

In many applications, they also rely on I/O performance. So we need to clearly define how to measure the performance and not get tangled up in all of the definitions and concepts. So let us declare something:

Total elapsed time will always be the one to determine our performance.

We should measure the total elapsed time first and then measure individual times to find where the bottleneck is.

CPU Execution time#

There is a concept introduced here: clock cycle (or tick, clock tick, clock period, clock cycle). It is a discrete time that relates or measures how fast basic functions are executed.

The inverse is called clock rate and the relationship between the cycles for a program and cycle time can be summarized by the formulas below.

$$ \text{CPU execution time} = \text{CPU clock cycles for a program} \times \text{Clock cycle time} $$

$$ \text{CPU execution time} = \frac{\text{CPU clock cycles for a program}}{ \text{Clock rate}} $$

We can see that to reduce execution time, we can either decrease the number of cycles for a program or increase the clock rate. However, we need to make sure decreasing the number of cycles don’t increase the clock rate or decreasing the clock rate doesn’t increase the number of cycles.

This is one example of why we should care about the elapsed time and not just measure performance in one dimension.

Wait, what even are clock cycles for a program? How do we measure that? Well, we know that processor executes instructions. Therefore, we can define cycles for a program to be the product of how many instructions the program needs and how long does it take to execute each instruction.

$$ \text{CPU clock cycles} = \text{Instructions for a program} \times \text{Average clock cycles per instruction} $$

The average clock cycles per instruction is abbreviated as CPI. Since CPI is different for different instructions, we take the average of all instructions executed in the program. CPI gives us a way to compare different ISA for the same program.

Now, we can combine the concepts and have the “classic CPU performance equation”:

$$ \text{CPU time} = \frac{\text{Instruction count}\times \text{CPI}}{\text{Clock rate}} $$

By default, we would know what the clock rate would be and we would know CPU time by measuring it. How do we know the instruction count? Well, the most accurate way to do that would be to actually measure it. And you can do that in software (by running a simulation) or directly in the hardware with the help of a counter.

Hardware can actually measure a variety of records, such as the number of instructions, average CPI, and even the sources of performance loss. This is the most reliable way because usually CPI depends on a lot of design choices: memory system and processor structure, as well as the program.

Here is some components that affect the CPU performance:

- Algorithm They determine the number of instructions as well as the type of instructions. For example, an algorithm that has more divides will have higher CPI.

- Programming language Statements in the language are translated to processor instructions (which determine the instruction count). Certain features also might affect - for example, Java has data abstraction that requires indirect calls, which results in higher CPI instructions

- Compiler

- Compiler converts source language instructions to machine instructions. So the compiler affects performance a lot.

- Instruction set architecture

- Affects all three aspect - instruction count, cpi and clock rate.

Traditionally, clock rate is fixed but some processors like Intel i7 temporarily increases the clock rate until the chip gets too warm.

The Power Wall#

Over the last 30 years, the clock rate and power increased rapidly but declined in the last few years due to one problem - the Power Wall. This comes from the inability to cool common microprocessors. Of course, there are ways to better cool the chips but it is an expensive solution and therefore - not scalable.

In the post-PC era, there is another problem with power. The devices are portable, which means the performance is limited by the battery.

CMOS is the transistor that we use for integrated circuits. It’s main energy consumption is the energy that requires it to switch from 0 to 1 and vice versa - what we call dynamic energy. The dynamic energy depends on the capacitive load and voltage applied.

$$ \text{Dynamic Energy} \space \alpha \space 1/2 \times \text{Capacitive load} \times Voltage^2 $$

$$ \text{Power} \space \alpha \space 1/2 \times \text{Capacitive load} \times Voltage^2 \times \text{Frequency switched}$$

Here, the capacitive load is a function of the fanout (number of transistors connected to output) and the technology. It determines the capacitance of both the wires and transistors.

In the last 30 years, clock rate grew by 1000 degrees while power consumption grew by only 30. That is because over the years, the voltage supplied decreased from 5V to 1V, and since power is proportional to voltage squared, we have such stark difference in increase.

So, why can’t we keep decreasing the voltage? The problem with that is it will make the transistors too leaky. Today, 40% of power consumption is due to leakage.

Now that we have hit the power wall, people are now focusing on different ways to make the processor more efficient.

The Sea Change#

Because we couldn’t improve due to Power Wall, the architects decided to ship microprocessors instead of trying to improve the performance of a single processor. The microprocessors contain multiple processors - called core in this case to avoid confusion. For example, quad microprocessors have 4 cores.

Previously, programs could increase in efficiency without a line of code being changed. But now with parallel processing, programmers need to be aware of the parallel nature of computers.

One way to use parallelism is pipelining, an instruction level parallelism. While parallelism was a very big stepping stone to get over power wall, there are so many reasons why it is a tool that must be handled carefully.

- It is performance programming. Most of the systems we have (especially legacy ones like banking) are not built on parallel programming, and the effort to make them is very expensive (much more expensive than having more servers) that it is better for them to just write sequential programs.

- For the program to make use of parallelism, it must divide the work equally, which might have some overhead that completely offsets the performance gained by parallelism.

To take advantage of parallelism, we need:- Scheduling: Each core must have something to do at the same time.

- Load balancing: If one core takes too long, the others would be waiting and the benefits would be gone. So, we need to divide the work in terms of load (how long it will take), not the number of jobs.

- Reducing communication and synchronization overhead: If a process at one core depends on the outcome of others, it would increase the time taken. Or if there is too frequent communication, this will also take resources away from actual computing.

There are some parallelism mentioned here, such as:

1. Chapter 2: Parallelism and Instructions - Synchronization

Synchronizing tasks (letting other cores know when they have completed their work)

2. Chapter 3: Parallelism and Computer Arithmetic - Sub word Parallelism

Computing elements in parallel (ex: multiplying two vectors)

3. Chapter 4: Parallelism via Instructions

Pipelining and Prediction

Fallacies and Pitfalls#

This section was one of my favorites. As the title suggest, the authors talked about fallacies - common misconceptions (conceptual or theoretical) and pitfalls - easily made mistakes (practical or implementation-related).

Overall improvement of the computer will be proportional to the improvement made on one aspect

Here, another concept was introduced - Amdahl’s Law. Amdahl’s Law says that the benefit of improving one part of a system—like making multiplication faster—is limited by how often that part is actually used.

Even a big speedup won’t help much if it’s only used occasionally. This reflects the idea of diminishing returns: the more you optimize something that isn’t used often, the less overall impact it has.

So the bottleneck of the program becomes the part that we didn’t optimize.

The author correlates the law to parallel computing. No matter how many cores we have, if some parts of the computation cannot be parallelized will be the bottleneck.

Computers at low utilization use little power

In 2012, 33% of peak power was used at 10% of the load. This is important because most of the time, server workloads are between 10-50% (in Google’s warehouse scale computers) and 100% at 1% of the time.

My opinion at this point in time (where I haven’t read the following chapters) would be that the reason we use so much power is due to leakage current. In the power wall section, it was mentioned that 40% of power consumption in chips today are due to leakage.

Optimizing for speed has no connection to optimizing for energy efficiency

Here, the explanation is simple, since energy is power over time, the less time you spend executing a program, the less energy you spend.

Judging performance based on only part of the full performance equation, instead of considering all contributing factors

It was emphasized a lot during performance section, that we should use clock rate, instruction count and CPI to evaluate. Skipping one or two factors is a common pitfall.

Authors brought in another alternative (performance metric) to time - MIPS or Millions of Instructions Per Second. This should not be confused with MIPS (Microprocessor without Interlocked Pipeline Stages).

MIPS is program execution rate, meaning higher the number, the faster the computer. But there are 3 problems with MIPS:

- Since MIPS only cares about the numbers and does not take account of CPI, it cannot be used to compare computers with different instruction sets.

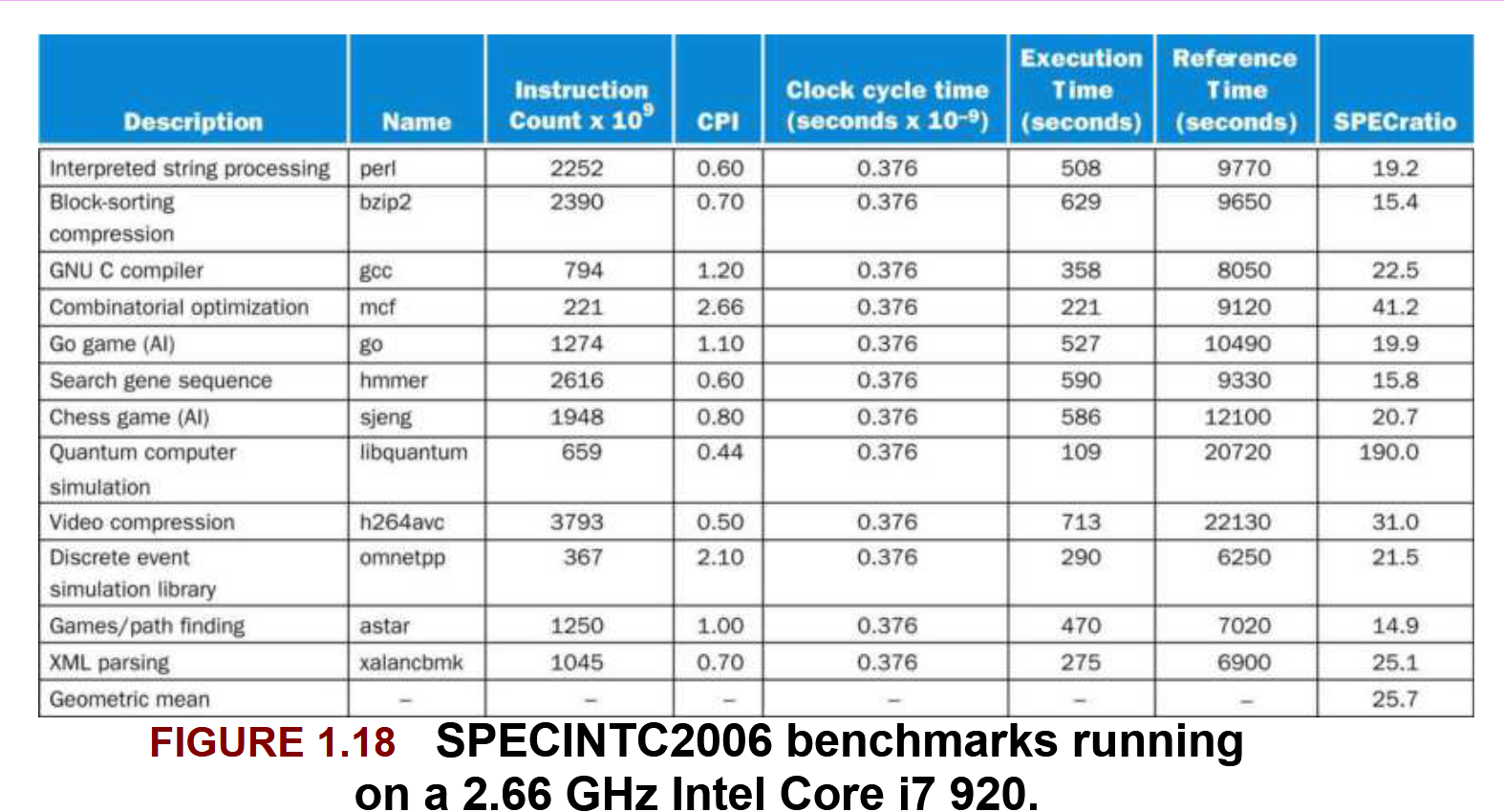

- MIPS varies from program to program, so we must use multiple MIPS. Figure 1.18 from the book:

- Program execution time varies independently of MIPS. If one program has more instructions but each instruction is faster, MIPS is different but independent of actual performance.

MIPS = Instruction count / (Execution time * 10^6)

References:

Hennessy, J. L., & Patterson, D. A. (2018). Computer Organization and Design: RISC-V Edition (2nd ed.). Morgan Kaufmann/Elsevier.