Part 3-1: Procedures

Procedures

Procedure or function is a tool that programmers use to structure a program. It is sequence of instructions that are reusable and easier to understand. It allows the programmers to concentrate on one portion of the task at a time. And it is one example of abstraction.

They communicate with the rest of the program using parameters. Parameters are an interface between them by passing values and return results.

There was a really good analogy in the book about procedures and I will leave it as it is.

Procedure acts like a spy who leaves with a secret plan, acquires resources, performs the task, covers their track and then returns to the point of origin with the desired result. They also act on “need to know” basis - they don’t question who the “master” is.

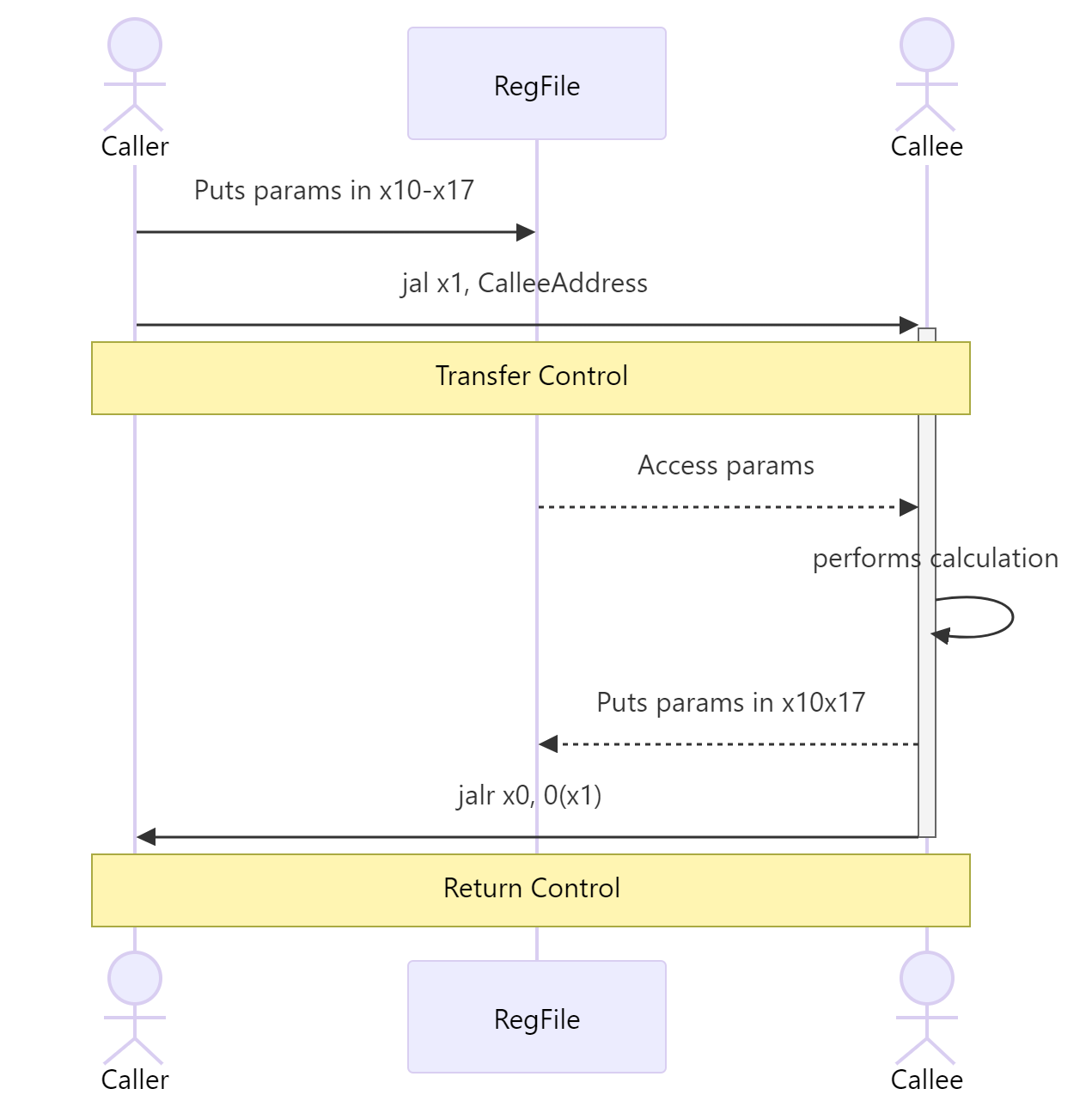

I have made a sequence diagram to kind of visualize what the program flow is when calling a procedure.

The caller in this case is the main program, essential someone who “called” the procedure. They place the parameters needed for the procedure in register x10-x17 and transfers control to the callee. The transferring control is done using the instruction jal x1, CalleeAddress. jal is short for jump and link and it is used in RISC V for indirect jumps.

Side note on control flow

It might be confusing with all the terminology about direct, indirect jump, conditional branching etc, so I made a table. Control-flow in RISC-V falls along two orthogonal axes:

- Condition:

- Conditional (branching only if a test is true)

- Unconditional (always taken)

- Target resolution:

- Direct (encoded offset/address)

- Indirect (address held in a register)

| Direct | Indirect | |

|---|---|---|

| Conditional | beq, bne, blt, bge | – (none in RISC-V) |

| Unconditional | jal, j | jalr, jr |

The callee (aka our procedure) then performs calculation, returns value to register x10-x17, and returns control back to the caller.

In a stored-program concept, we always need to have a register to hold the address of the current instruction being executed. Why? Well, let’s do a thought experiment. Without program counters, how far can we go in terms of complexity? Finite state machines. If we don’t have the ability to track which instruction is currently being executed, then we can just cycle through states with predetermined behavior associated with them. The hardware will not be reusable at all.

In a stored-program concept, we always need to have a register to hold the address of the current instruction being executed. Why? Well, let’s do a thought experiment. Without program counters, how far can we go in terms of complexity? Finite state machines. If we don’t have the ability to track which instruction is currently being executed, then we can just cycle through states with predetermined behavior associated with them. The hardware will not be reusable at all.

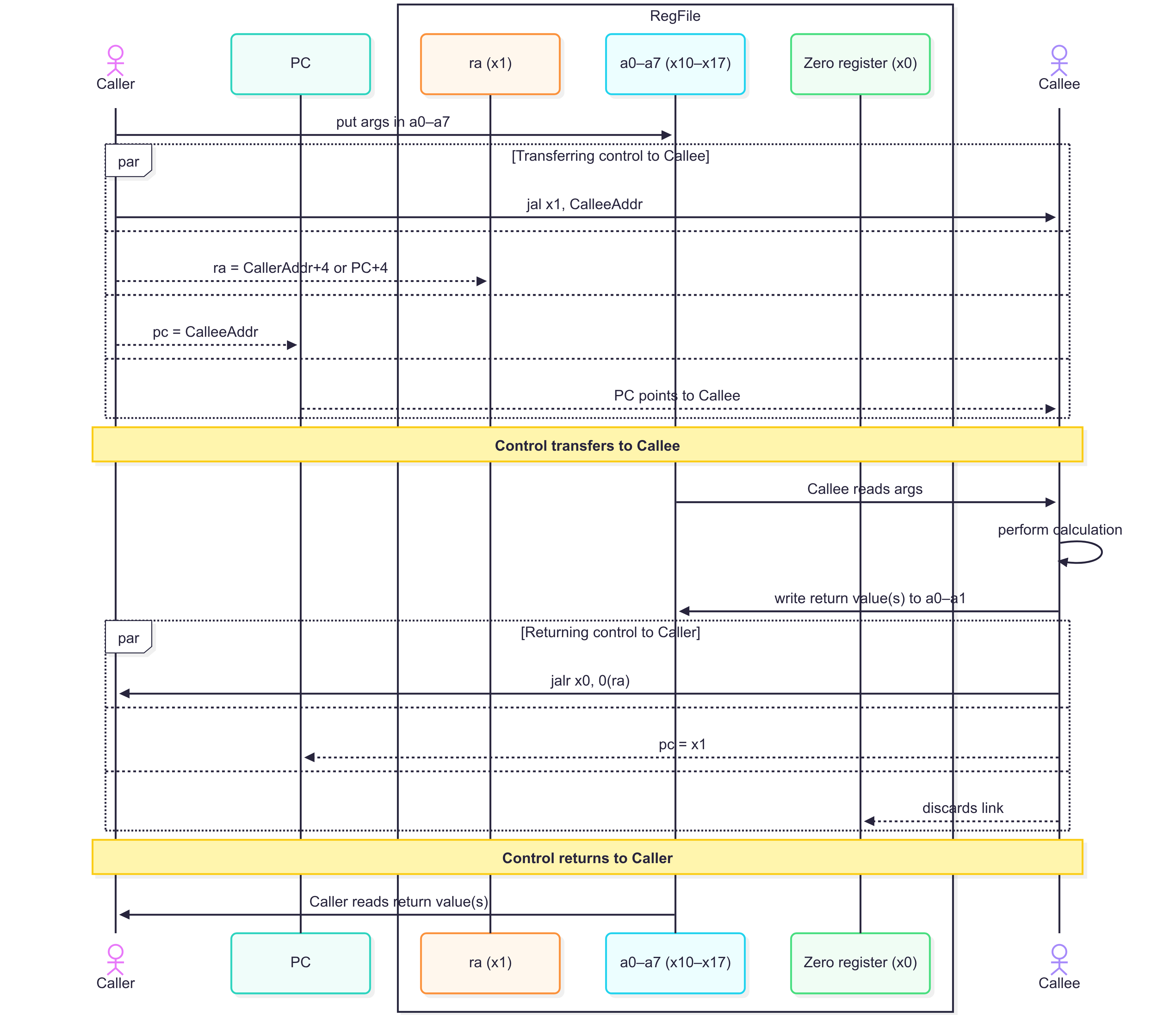

With the addition of PC, the sequence diagram would look a bit more complicated. But it is essentially doing the same thing. Main difference is that now we have partitioned our register file to specific registers (x1 for return address/ra or program counter/pc). This demystifies our register file a bit. And having the concept of program counter is very essential to computing, and would help understanding the program flow in more complex procedure calls (like recursive functions).

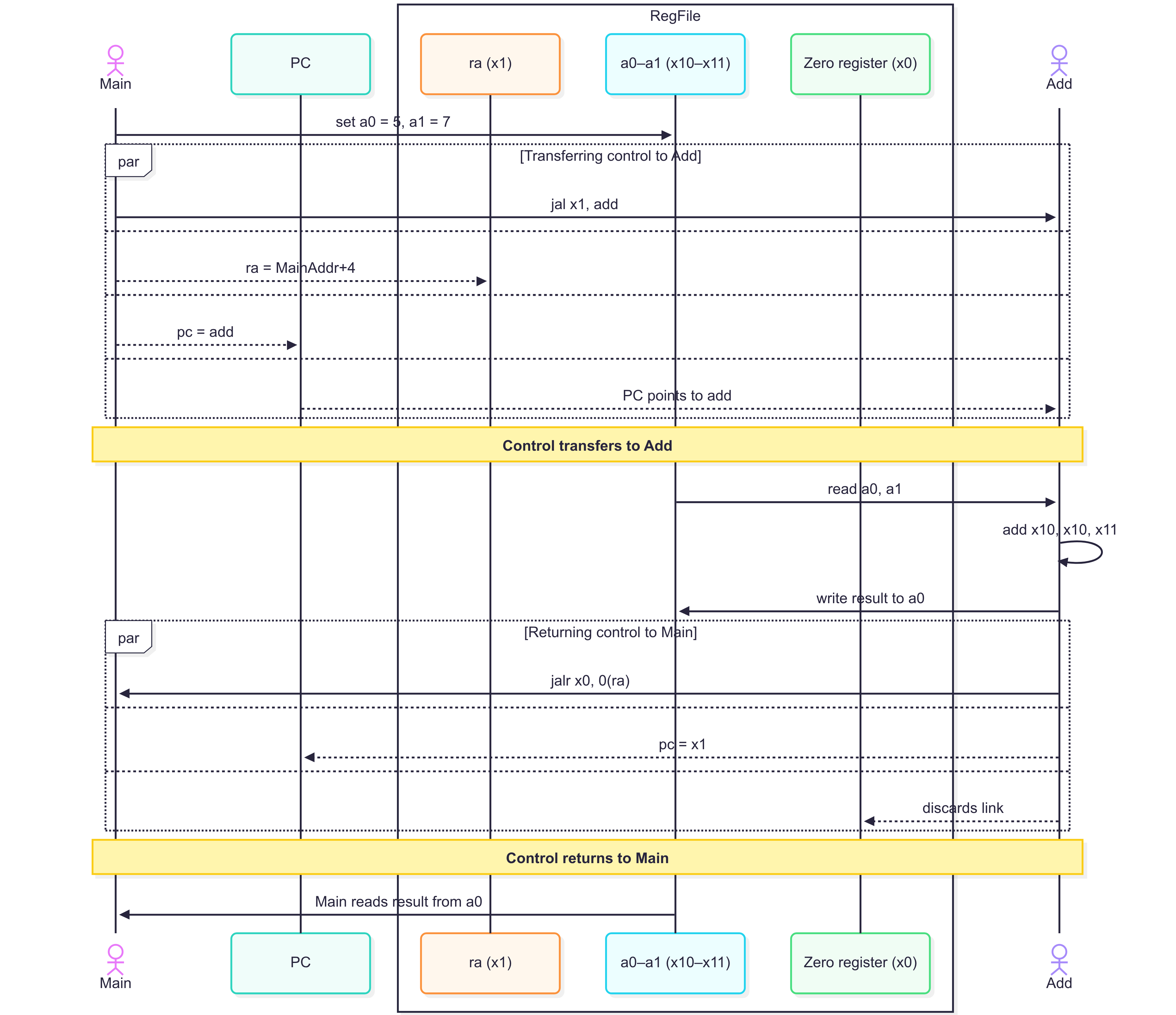

Now that we can call a basic procedure, maybe we can look at an assembly code. Here is an example.

.section .text

.globl main

main:

# prepare arguments

li x10, 5 # x10 (a0) = 5

li x11, 7 # x11 (a1) = 7

# call leaf procedure 'add'

jal x1, add # x1 (ra) ← PC+4; PC ← add

# on return, x10 holds result (5 + 7 = 12)

# exit via ecall (Linux)

li x17, 93 # x17 (a7) = 93 (sys_exit)

ecall

# Leaf procedure: adds x10 + x11, returns in x10

add:

add x10, x10, x11 # x10 = x10 + x11

jalr x0, 0(x1) # PC ← x1; return (x0 discards link)The code is displayed as a diagram here.

Using more registers

Okay, well now we can call small procedures. But what if we need to pass more parameters? If we use more register, we would violate our procedure requirements - that when you return control to the caller, there should be no residue (we would have to cover our tracks). In this case, we would need to involve the memory. This is called spilling the register to memory.

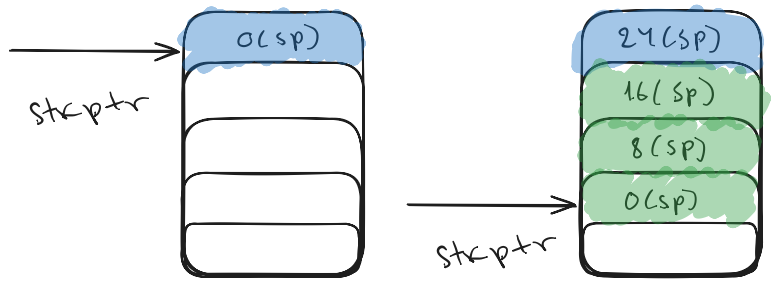

The data structure we use to spill memory is stack. A stack is a region of memory that grows and shrinks as you need it. You “push” values onto the stack to save them and “pop” them off to restore them. It works in a last-in, first-out order, like a stack of plates.

In RISC-V we use the stack pointer (sp saved at register x2) to reserve space before a call and release it after. The stack grows from higher addresses, so to “push” to stack you would have to subtract 8 bytes from the address of stkptr and store the data on memory at stkptr.

Similar to that if we want to store 3 variables (dw), then we subtract 24 bytes and then store the variables in addresses: 16(sp), 8(sp), 0(sp).

Example code:

.text

.globl main

main:

# — load first eight args into a0–a7

li a0, 1 # b

li a1, 2 # c

li a2, 3 # d

li a3, 4 # e

li a4, 5 # f

li a5, 6 # g

li a6, 7 # h

li a7, 8 # i

# — spill 9th arg (j) at 0(sp)

li t0, 9 # j

addi sp, sp, -4 # allocate 4 bytes

sw t0, 0(sp)

# — call calc; return value → a0

jal ra, calc

# — restore stack

lw t0, 0(sp)

addi sp, sp, 4

# — exit (Linux syscall)

mv a0, zero # return code 0

li a7, 93

ecall

calc:

# a0..a7 = b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i ; j is at 0(sp)

lw t0, 0(sp) # t0 ← j

add t1, a0, a1 # t1 = b + c

sub t2, a2, a3 # t2 = d – e

mul t1, t1, t2 # t1 = (b+c)*(d–e)

add t2, a4, a5 # t2 = f + g

sub t3, a6, a7 # t3 = h – i

mul t2, t2, t3 # t2 = (f+g)*(h–i)

add t1, t1, t2 # t1 = sum of products

add t1, t1, t0 # t1 += j

mv a0, t1 # return value

ret # jalr x0,0(ra)The parts you have to pay attention to are that we spill the register for the 9th parameter by doing some arithmetic on sp. Then after the procedure is called, we restore the value from the stack and adjusts stack pointer. The restoring action is important because otherwise we will corrupt the stack pointer. Once the stack is corrupted, you’ll see crashes, wrong results, or unstable, unpredictable behavior.

And you can also see t0-t3 here. They are part of what is called temporary registers(x5-x7 and x28-x31). These registers’ values are not preserved by the callee. However, s0-s11 (x8-x9 and x18-x27) values are preserved by the callee.

Nested procedures

We have basic understanding of procedures now, but these are only leaf procedures. They are procedures that do not call any procedures. However, there are procedures that call other procedures - one sparkling example of this is recursive function. They invoke copies of themselves.

But when you have nested calls, you have contention over the register. For example, x1 stores the return address, when the first procedure is called, the caller address is saved in x1. But when the procedure calls another procedure, the address of the first procedure is saved in x1. Now, we have lost our initial caller’s address. The link is broken. Similar problems may arise with parameters. So whenever there is a nested procedure, you have to pay a very close attention to the register. (This is also true in any function, pay attention to registers)

To solve this, use the stack: push every register that must be preserved before a call. The caller should save the argument registers (x10–x17) and temporaries (x5–x7, x28–x31), while the callee should save the return address (x1) and the saved registers (x8–x9, x18–x27).

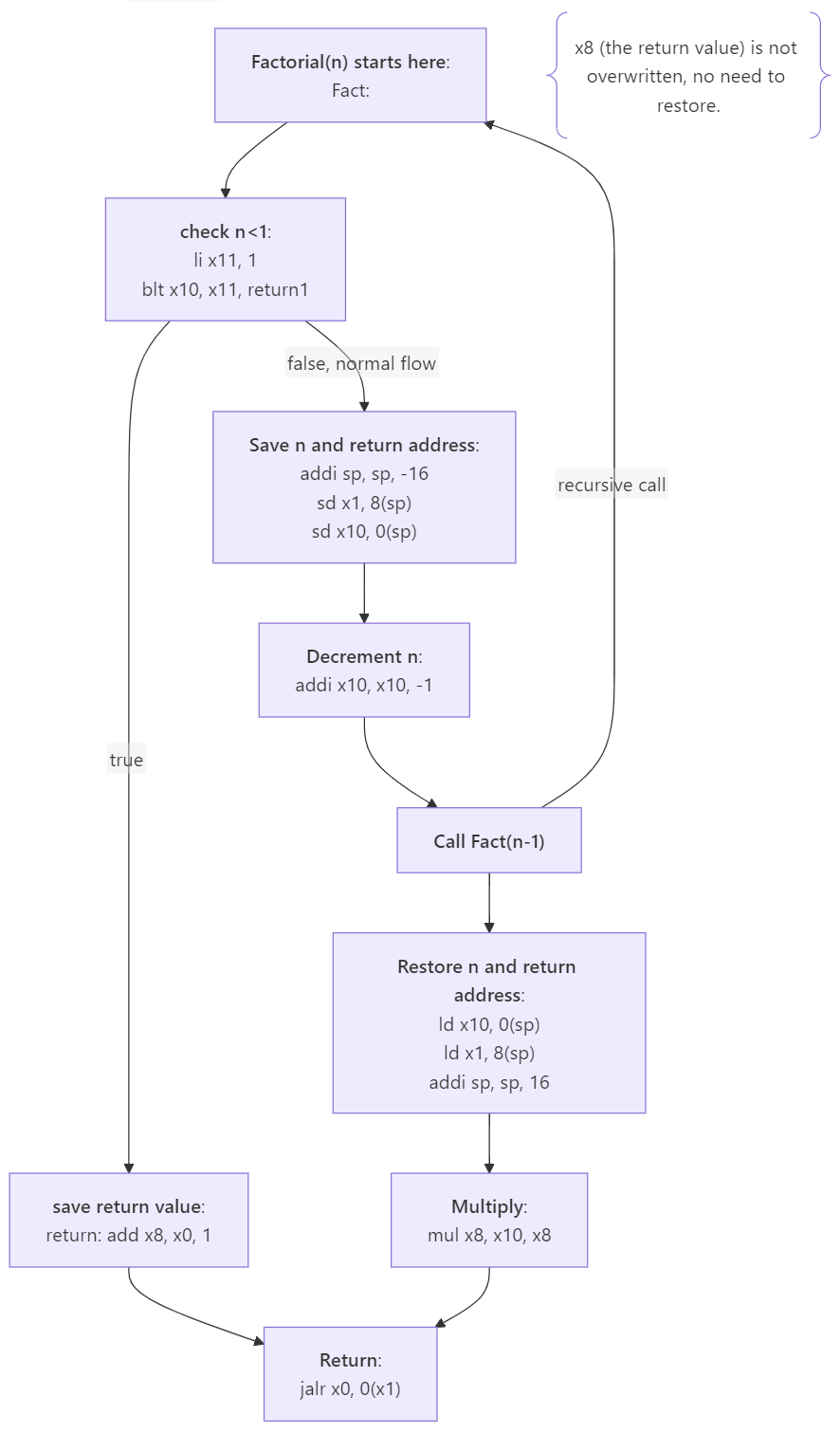

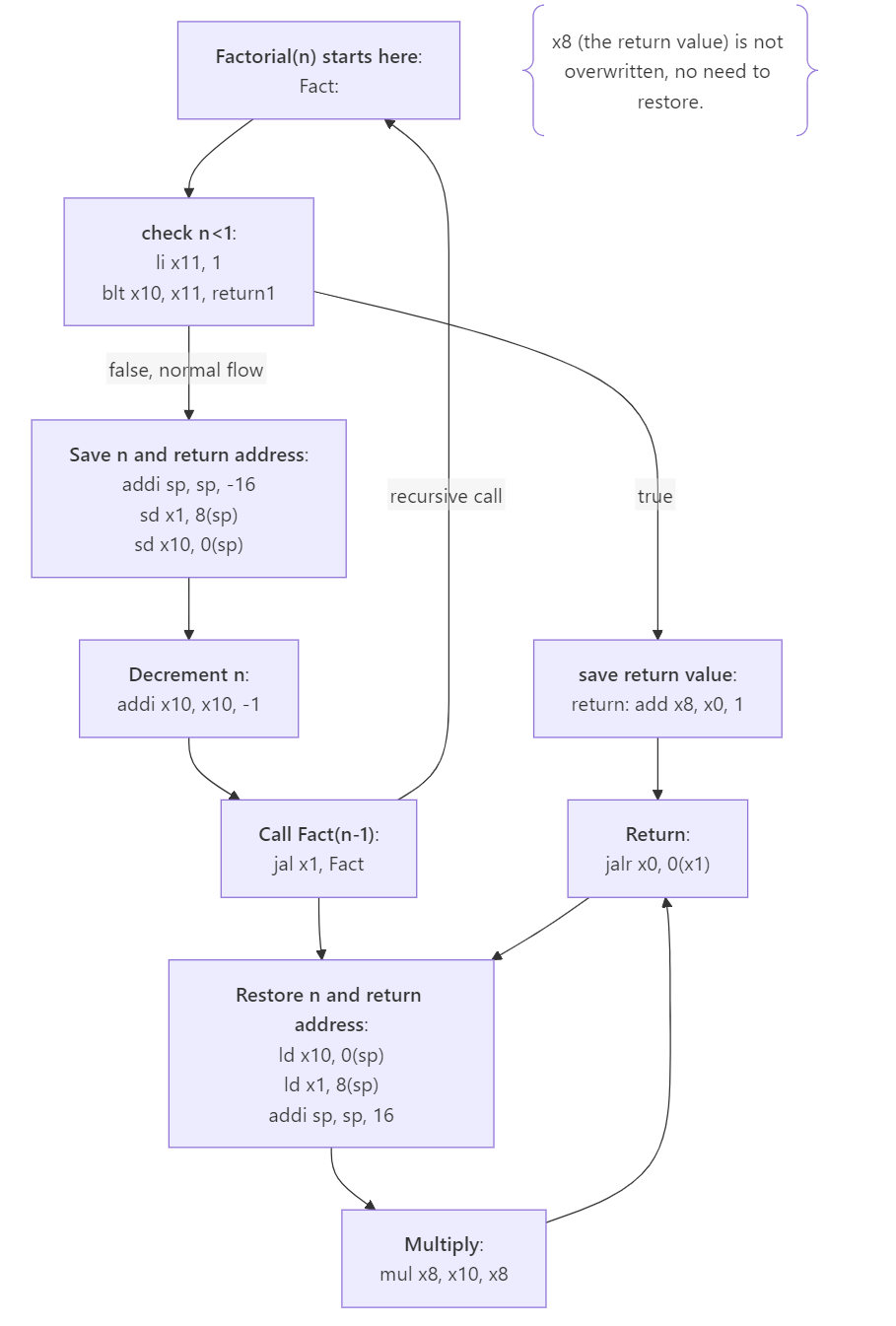

Let’s try with factorial function.

long long int fact (long long int n)

{

if (n<1) return (1);

else return (n * fact(n-1));

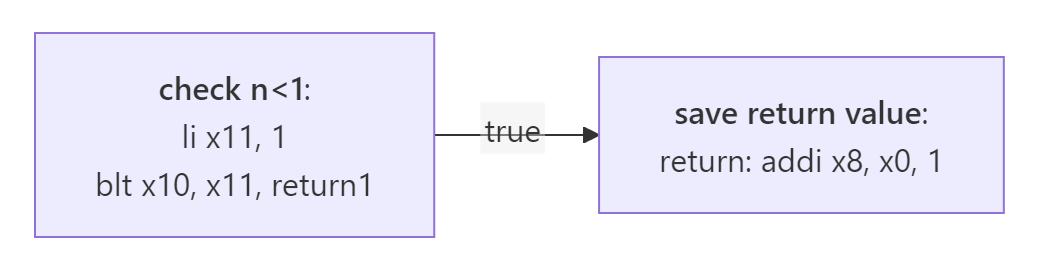

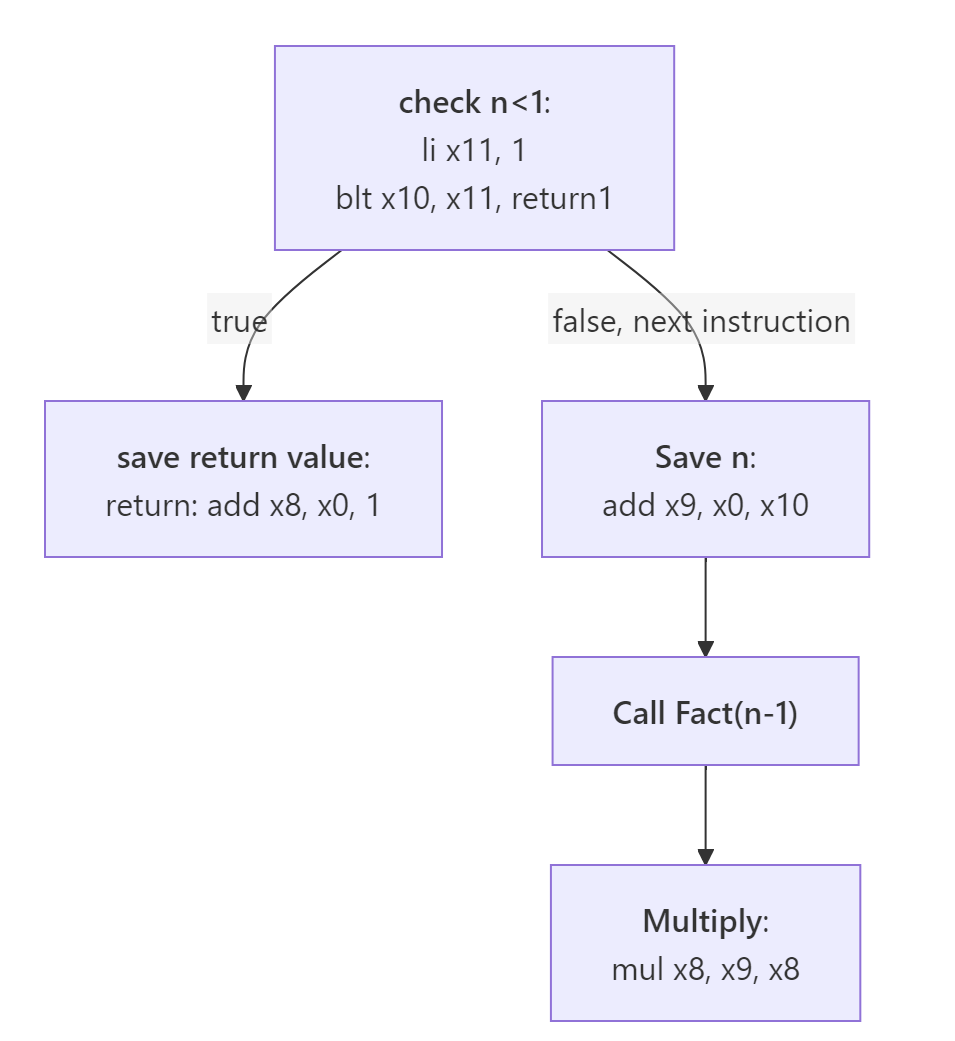

}Let’s start with the first part which is checking if $n<1$ and returning 1 if it is:

Here, we are storing our parameter n in x10, and x8 is a saved argument. Then let’s go to the next logic.

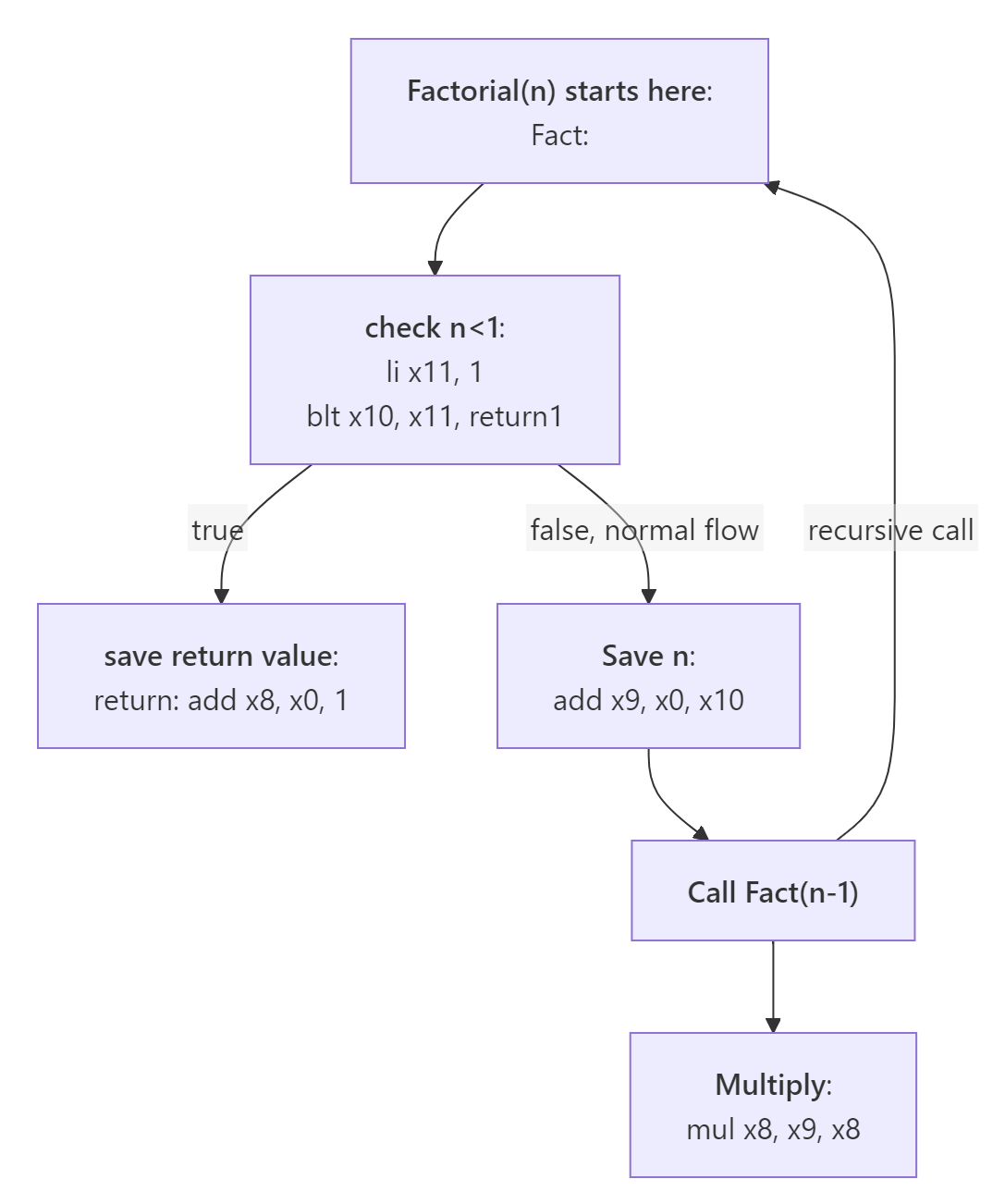

Now if you have looked at the flowchart, we have one problem. Calling the fact(n-1), so we add a label here.

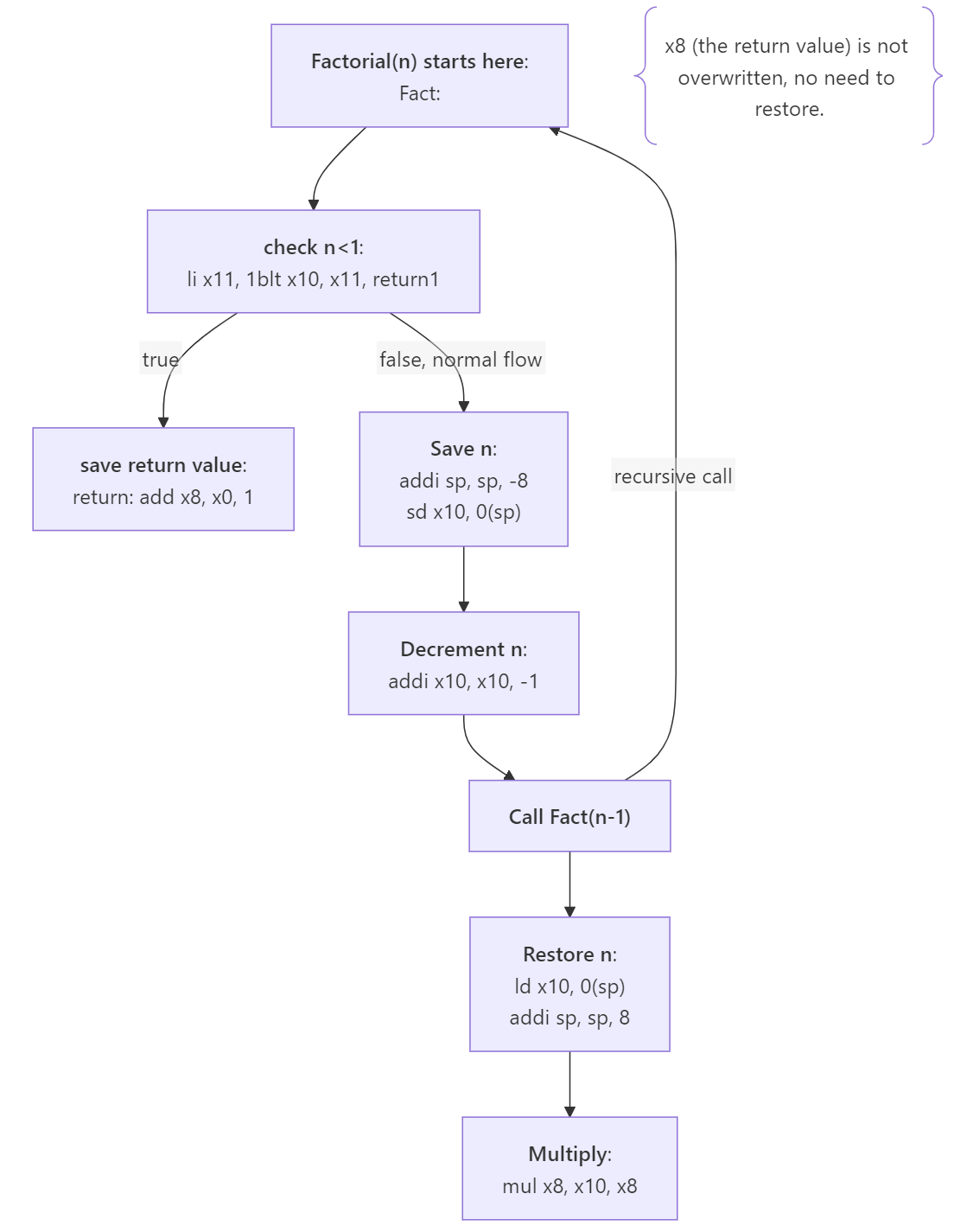

Okay, great! Now the hard part which is preparation before and after the recursive call. We can’t have any useful value on the registers before calling another procedure as it might get overwritten. So let’s replace

Okay, great! Now the hard part which is preparation before and after the recursive call. We can’t have any useful value on the registers before calling another procedure as it might get overwritten. So let’s replace add x9, x0, x10 with

addi sp, sp, -8

sd x10, 0(sp)Since we are saving them we should also restore from the sp after call Fact(n-1)

ld x10, 0(sp)

addi sp, sp, 8And we should also make sure that we decrement x10 before calling Fact(n-1).

This is mostly correct. But we (more specifically I) forgot one major thing. The return address stored at x1. For the leaf procedure (case where n<1), we don’t need to store anything since our x1 value (link) is the correct one, so we can just jump back.

jalr x0, 0(x1)But for the other case, we have to first push to stack before calling Fact(n-1) and restore after multiply.

We can also replace call fact(n-1) with its actual instruction and point return to the value of x1, or where we will return to.

We can also replace call fact(n-1) with its actual instruction and point return to the value of x1, or where we will return to.

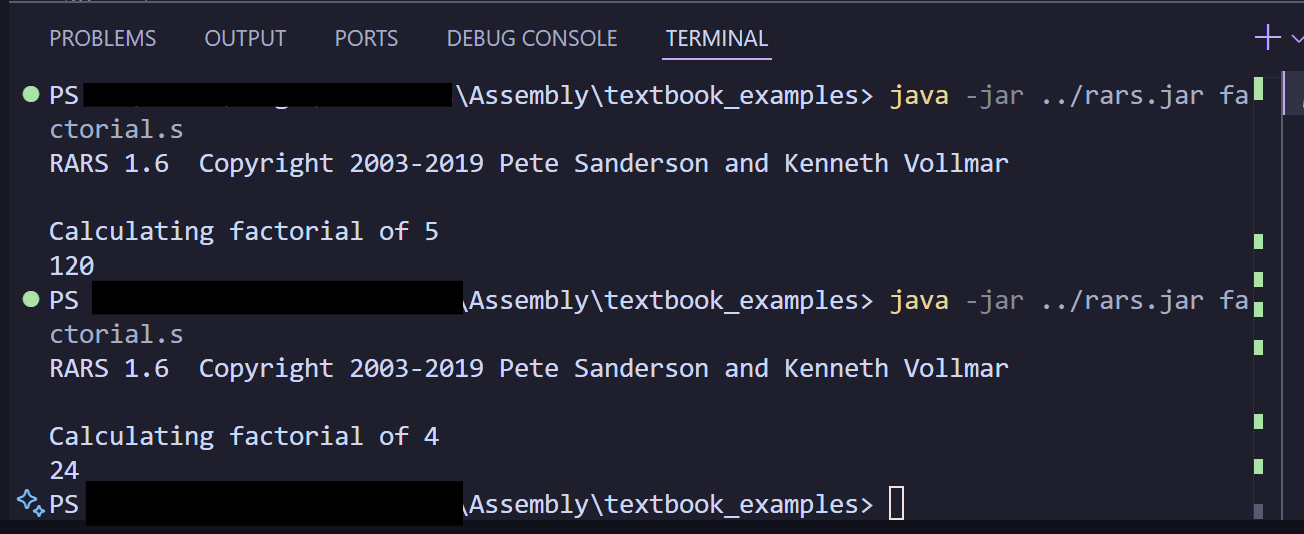

Great! Now we can turn it into actual assembly code and see if it works:

Great! Now we can turn it into actual assembly code and see if it works:

fact:

li x11, 1

blt x10, x11, return1

addi sp, sp, -16

sw x1, 8(sp)

sw x10, 0(sp)

addi x10, x10, -1

jal x1, fact

lw x10, 0(sp)

lw x1, 8(sp)

addi sp, sp, 16

mul x8, x10, x8

jalr x0, 0(x1)

return1:

addi x8, x0, 1

jalr x0, 0(x1)It works yay!

Okay, now we can conclude our very long session on nested procedures. This is a very interesting chapter so far and I would like to mention that I made all the diagrams here and am very proud of that. :D Next, we shall march on to learn more about the memory.