Register File in RISC V

Registers are the literal beating heart of any CPU. Think of them as the processor’s ultra-fast scratch pads—tiny storage locations built from flip-flops or register cells—holding the active data your instructions operate on.

Bunch of these registers come together (32 in our case and most RISC V cores) to make a register file. The register file is just a wrapper that helps us index into (modify and read from) the registers.

1. What Is a Register File?

A register file is a small, dedicated bank of storage inside the CPU that holds all architectural registers (x0–x31 in RV32I). Unlike main memory (DRAM/SRAM) accessed via load/store, the register file sits directly in the datapath:

Two read ports: Let the ALU grab two source operands in parallel. Reads are asynchronous (combinational), so outputs update immediately when you change the read-address lines.

One write port: Feeds back the ALU (or load) result into the file on the rising edge of the clock. Writes are synchronous, happening only at

posedge clkwhenregwriteis high.

Internally, the file is just an array of 32 registers, each 32 bits wide, indexed by 5-bit addresses (because log2(32)=5).

2. Why 32 Registers? The RISC-V Trade-off

The choice of 32 registers is baked into the RISC-V ISA encoding:

Every instruction is 32 bits long.

Each register specifier (rs1, rs2, rd) gets exactly 5 bits in the instruction format.

2⁵ = 32, so you can index x0 through x31.

This balance—enough registers to keep frequently used data close, yet small enough to fit encoding space—keeps both hardware simple and instructions compact.

3. The Special Zero Register (x0)

RISC-V reserves x0 as a constant zero. Reads from x0 always return 0, and any write attempt to x0 is silently ignored in the write-enable logic:

if (regwrite && write_reg != 5'd0)

regs[write_reg] <= write_data;This hardware shortcut makes common operations—like adding zero or using x0 in branches—both efficient and free of special-case instructions.

4. Instruction Formats vs. Register Types

When you hear “R-type,” “I-type,” “S-type,” etc., that’s referring to instruction formats, not different register banks. All integer registers live in the same file. The formats simply allocate bits:

R-type: rs1, rs2 (two sources), rd (destination), plus funct3/funct7 for opcodes.

I-type: rs1, rd, plus a 12-bit immediate.

S-type: rs1 (base), rs2 (data), split immediate fields.

B-type: rs1, rs2, branch offset.

U-type: rd, upper 20-bit immediate.

J-type: rd, jump offset.

Each register field is 5 bits, always pointing to x0–x31.

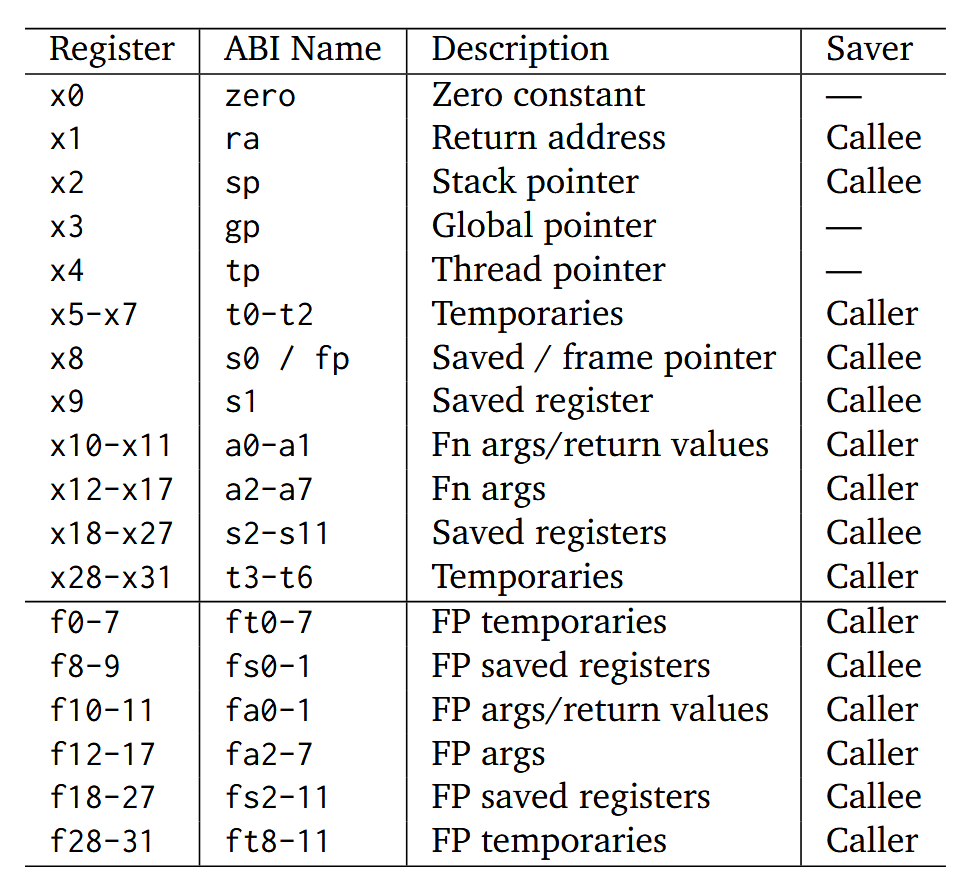

Reference Table:

- Caller-saved means: if a function (“caller”) wants to keep a value across a call, it must save it before calling and restore it after.

- Callee-saved means: the called function (“callee”) must save these on entry (e.g. push to stack) and restore them before returning—so the caller sees them unchanged.

- FP means floating point registers

- Temporaries (

t*): you can trash these in your function, but if the caller needs them later it must save them. - Saved (

s*): your function must preserve these so the caller finds them unchanged.

References:

https://www.cs.sfu.ca/~ashriram/Courses/CS295/assets/notebooks/RISCV/RISCV_CARD.pdf